Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

01.06.2022

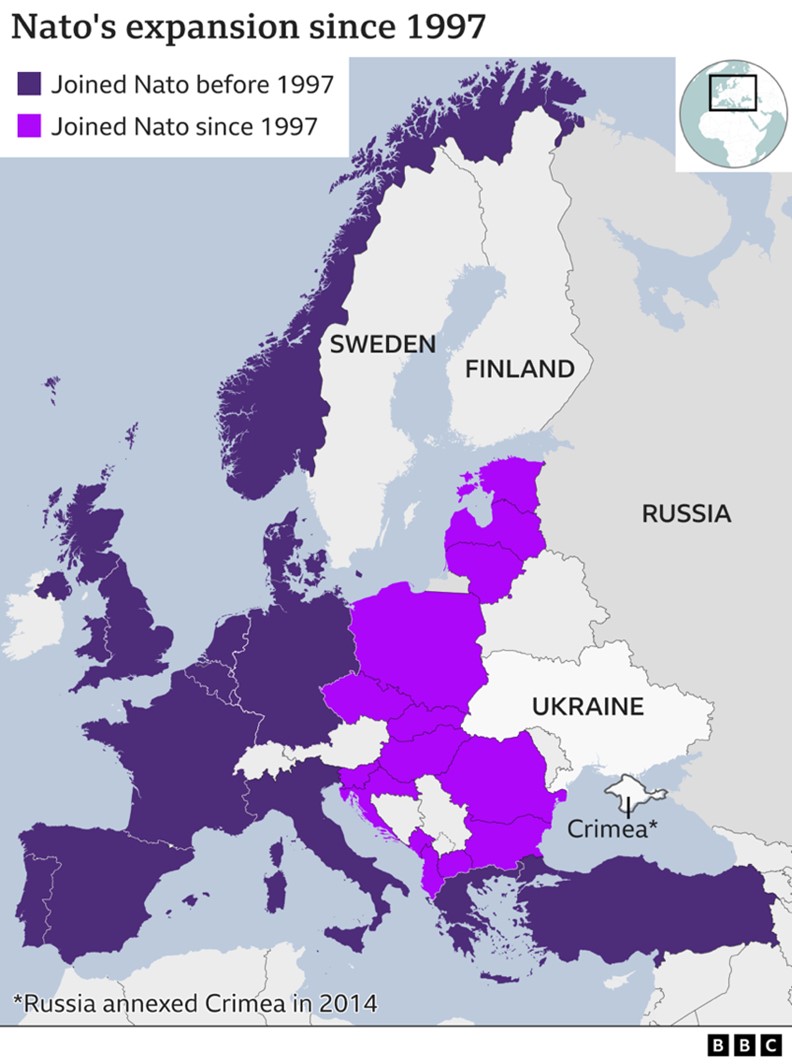

The Father to NATO's Ninth Expansion

As members of the European Union who remained outside NATO, Sweden and Finland had steered their foreign policy along a peculiar axis of neutrality — if you consider it from the standpoint of permanent military alliances. This does not mean their Defence budgets have dwindled, or that they have given up on national military service. In fact, the two political systems displayed signs of strategic evolution right after the close of the Cold War when they joined NATO's Partnership for Peace Programme in 1994, alongside with Eastern European, Balkan and Central Asian states, and even Russia itself. That partnership ring came to represent a precursor for NATO membership, progressively aligning political commitments, technical means and regular exercises shared among those countries, and NATO standards.

The relationship with Russia began to deteriorate, and things took a definite turn for the worse when Russia invaded and annexed Crimea in 2014. Threat perception levels went up as soon as the security architecture negotiated after the Soviet implosion fell apart, which is to say, the minute Putin tore through the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, wherein the territorial integrity of post-soviet Ukraine was ensured by a multilateral agreement in exchange for its controlled denuclearization. Russia not only violated treaties but it also saw its bold moves rewarded by the West's timid gestures. The localized conflict festering in Eastern Ukraine since 2014 consolidated threat perceptions with variable geometries from the Baltic to the Scandinavian countries. The European far-right, backed by Moscow, and the misinformation and cyber warfare campaigns waged all the while, completed Putin's siege of Europe. Unsurprisingly, polls in Sweden and Finland showed an increased preference for joining NATO. Many of their leading parties, as well as lawmakers and military leaders publicly aired their growing openness to the notion of joining the alliance.

In 2017, when I visited Stockholm and met with politicians, journalists and analysts, I perceived two parallel dynamics that impacted national security. One was expressed through Russia's bullying, be it via disinformation, or discursive domination over any mentions of any state joining NATO, and Russia's numerous submarine incursions just off Stockholm and military flights over Swedish airspace. In March 2017, Sweden announced it would restore mandatory national military service, a legal framework which had been repealed in 2010 after 109 of continued enforcement.

Another dynamic arose from the hectic shambling of Brexit. The UK leaving the European Union marked the end of an era where non-NATO-member Scandinavian states could comfortably hide their positions behind Britain’s — on common defence for the Union, among so many others. Brexit would force Stockholm to make more assertive decisions and respond to the tendency to centre the Union around the Franco-German dyad. This growing willingness to join NATO stems from this angle. Over the past few months, the materialization of a clear Russian threat in Ukraine and uncertainty as to Russia’s inclination to deploy her nuclear arsenal have put everyone on their toes.

Again in 2017, I visited Helsinki. I met a number of people so I could get a grip on the national conversation and Finns’ perception on leading European dynamics. Finland commemorated its hundredth year of independence then. It became clear to me that, in addition to the pillar that is education, the military provided a structuring factor in the State's constitutional consolidation and the feeling of national belonging. National security is one topic all Finns rally around. At a time of emerging threats, such as information wars, it is meaningful for governments to divulge and disseminate security awareness among their citizens. Defence is seen as a collective responsibility in Finland, and willingness to fight for the country shows higher (71%) in Finland than in other European countries. Stories about Finnish soldiers fighting Soviets have created a legacy of heroism that still inspires heightened commitment to the defence of freedom and liberty.

Collectivism is a mainstay for anything concerning security. The Finnish example suggests that one can balance individualism and collectivism. A great heritage of consensus and coalition cabinets facilitates that equilibrium, although it does not completely explain it — a common vision for national security and the will to cooperate on key matters is more than enough. That very year of 2017, and unsurprisingly so, Finland decided to host the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, focused on analysing current forms of conflict, from conventional to cybernetic warfare. Even then the initiative targeted Moscow. Again, in Finland, the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the war in Ukraine laid bare regional vulnerabilities and roused national consciousness. Finland and Russia share a 1300km border, which necessitates political channels & links to the Kremlin, a need Finnish president Sauli Niinisto has never overlooked.

A contextual look at these two countries and their security postures, foreign policies and growing threat perceptions will help you understand that it would only be natural to formalize their accession to NATO in 2022, after the invasion of Ukraine. European security has extended its reach to the North, closing off one more gap, bringing into the fold two contributors that align both technically and politically with NATO, which will add strength to its European roster. To Putin we owe the ninth expansion of NATO.

China and the zero-Covid mirage

Locking up 25 million people in Shanghai over the past quarter of 2022 and then extending the lockdown to four dozen cities may tell us more about Xi Jinping than we thought we knew. Right off the bat: he can get disoriented relatively easily. The number of new Covid infections provided no justification for the kind of general, protracted lockdown we witnessed — depriving people of staples and necessities, fanning the flames of despair, and feeding resentment against authority.

Fuel imports in international markets have dropped to 2020 levels, namely of liquefied natural gas, which will impact not only price fluctuations but also the slump in internal and external aviation numbers. The lull in commodity imports was paralleled by a bottleneck at the Shanghai port, the largest in the world, labour scarcity (which holds up unloading formalities), consignments stuck on ships (such as copper and iron ore), which delays ore processing for industry and trade — not to mention that ore processing concerns have seen their output deflate to as little as 40% in March alone. One consequence of draconian health measures could be delocalization: moving pre-planned investments to other countries, which not only adds a new cycle of unpredictability to the Chinese economy, as counterpoint to the stability China offered to businesses over the past two decades but may also drive down the appetite for closer ties with China in places like Europe.

With low vaccination rates among seniors in a country that produces vaccines, the zero-Covid strategy has proved itself a roadblock to China's economic recovery. It now shows its weakest growth in thirty years, a consequence of brutal disruptions to logistics. The number of ships held up in Shanghai went up by 160%. Inflation is guaranteed to rise and that will have global repercussions. All this chaos holds up a mirror to the political fragility of a chairman who intends the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party as the corollary to a decade of unassailable imperial power. However, we have witnessed doubts blooming in shadow about Xi Jinping’s ability to turn over a new leaf with the might of a great, mobilizing power.

Maybe this means that strong men like Xi or Putin don't have all the advantages and lack the tools to arbitrarily enforce their wills anytime, anywhere. Censorship of facts that inconvenience their regimes, such as recurring social upheaval, even guidance from international organizations like the WHO, is a favoured approach both in Beijing and Moscow. One they use to bend narratives around their decisions, even if they harm society. Such acritical inflexibility is commonplace in dictatorships.

Pandemic or warfare, it makes no difference: ossified absolutism, rather than course correction as needed, is the norm. We may have overrated these leaders out of instinct more than rational analysis, merely because they lead vast territories, mountains of resources and multitudes that cheer them on. The tools are all there, no doubt. What isn't quite there is judgment perfected as an aid to key political decisions, capable of overcoming personal weaknesses and put those countries on paths that would garner them respect and admiration from the rest of the world. So this is a defining moment for the future of authoritarian systems. Not just for democracies, as we tend to think almost exclusively.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.